Short answer: I've never heard of such a thing, but it's hard to prove a negative.

Longer answer: every linguistic theory I know of agrees on a few fundamental points, which are sometimes called linguistic universals. These are features that appear in every single language in the world; if you believe in universal grammar, these are part of it. It seems fairly clear that these features also have specific mechanisms in the brain: look into Broca's aphasia and Wernicke's aphasia (or ask another question here if you prefer!) for details on how we know this.

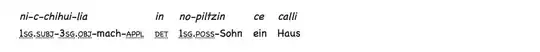

Some of these features are almost trivially straightforward: for example, every language has a set of lexical items (words, morphemes, etc), and every language divides these lexical items into different classes that follow the same general patterns.

But one feature that isn't as straightforward, and according to Hofstadter might be tied in to the basis of consciousness itself, is recursion. In other words, every language in the world has the ability to take a thing of type X and a thing of type Y and put them together to make a thing of type Z. And in particular, recursion involves the ability to combine an X and a Y to make another X. This seems to be a fundamental property of language, and possibly built into the way our brain handles language at the most basic level. (*)

For a concrete example, consider the phrase "the gazebo". Some theories call it an NP, while others call it a DP, but the label doesn't matter. Now consider the phrase "the pineapple". You can combine these with the word "and" to make the phrase "the gazebo and the pineapple", which has the same general type as both of the phrases making it up: you can use it in the same place in a sentence.

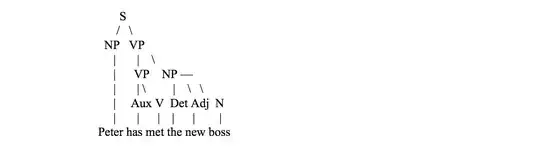

The fact that you can put together an X and a Y to make a Z lends itself well to a tree structure. That's simply what trees do. There are several different ways to make the tree: phrase structure grammar talks about it in terms of "X + Y = Z", while a dependency grammar talks instead about the relationship between the X and the Y, and a lambda-calculus based model like you see in semantics will talk about a function taking a tuple (X, Y) and returning a Z. But no matter how you phrase it (pun intended), there's some sort of tree structure at work.

Do you have to draw it as a tree? Not at all. You could use commas and brackets instead, like the function-y theories do. But it expresses the same basic model.

Do you have to think about it as a tree? Nothing forces you to. But linguists have found that trees are an exceptionally useful model for this, which may come down to the innate way our brains actually process language. So no modern theory without trees of any sort has really caught on.

(*) Some people claim that one obscure language from South America, Pirahã, lacks recursion. But the evidence on this is somewhat lacking, only one researcher has the data to back up this claim, and there are some reasons to question his data and methods. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and I haven't seen enough evidence to justify "this language is different from literally every other language we've ever seen on Earth". So I'm disregarding it.